Italy in the XIII century appeared to Olivi to be devastated by wars and secessions, preliminary signs of the advent of the Antichrist. Rome, the Papal See to which Francis had vowed obedience, was a concurrently a historic and an ideal city, the civitas solis in Isaias 19:18, which the Catholic Fathers called the whore. Augustinianly there were actually two churches, one of the Righteous and the other of the Reprobates who wander and fight both in the city of Rome and throughout the Roman Empire. Olivi did not exclude that Christ may move “Rome” and reinstate his See in Jerusalem or in another venue when the Antichrist has been defeated.

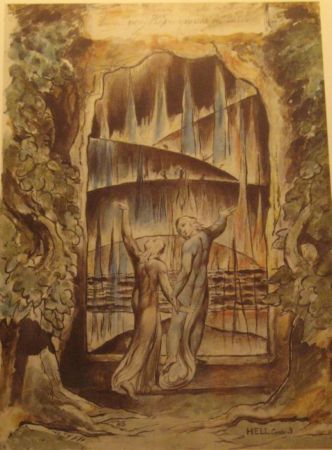

The greatest and almost immediate influence that Olivi the exegete and above all the Lectura super Apocalipsim had on Italy was the creation of the vernacular in Dante’s Commedia. Ernesto Buonaiuti, Raoul Manselli and Ovidio Capitani have already compared the two texts, although they only covered the authors’ affinity of ideas and a few passages of the Commedia. A discovery made during twenty years of research proves that there is indeed a technical relationship that concerns the entire poem and each of the 14233 hendecasyllables, in which the theological concepts have been established and transformed. This extraordinary textual metamorphosis is based on specific and verifiable rules, prerequisite to any consequent considerations.

The Divina Commedia is a universe of signs. The literal meaning contains keywords to access another text, the Lectura super Apocalipsim by Olivi. This is a technique used in the art of memory: like imagines agentes the keywords remind readers of a doctrinal book they have read before, which they mentally reread paraphrased in the vernacular, extensively updated according to the poet’s intent, in verses that lend “e piedi e mano” to the doctrine and provide contemporary and familiar exempla.

The literal sense of the “sacred poem”, intended for readers in general, also contains allegorical, moral and anagogic meanings (which Dante collectively defined as ‘mystical’ or ‘allegorical’ in his Letter to Cangrande). Dante, who considered himself a new Saint John and his work a new Apocalypse, targeted a readership of seculars, as well as preachers and Church reformers. The clerical readership failed to develop because the Spirituals (a loosely organised movement within the Franciscan Order), who should have known Olivi’s Lectura, were persecuted and their book-vexillum, which was censured in 1318-1319 and condemned in 1326, became clandestine and almost disappeared. However, the Commedia and the Lectura were textually related and the last witnesses, in the Christian Middle Ages, of the way individuals were placed in the world order according to the judgment of God and the history of collective salvation, before man was left alone.

[ALBERTO FORNI, Pietro di Giovanni Olivi nella penisola italiana: immagine e influssi tra letteratura e storia in Pietro di Giovanni Olivi frate minore. Atti del XLIII Convegno Internazionale. Assisi 16-18 ottobre 2015, Spoleto 2016 (Società Internazionale di Studi Francescani – Centro Interuniversitario di Studi Francescani), pp. 395-437. Translation by Susan Aulton.] Read more.

[739 KB]